War and Peace, free will, and how change happens

“Why do wars happen? We don't know.” War and Peace is an attempt to understand the arc of history. Tolstoy collides at the junction of free will and determinism, helps us understand life amidst chaos.

War and Peace has a terrible ending, whichever way you cut it.

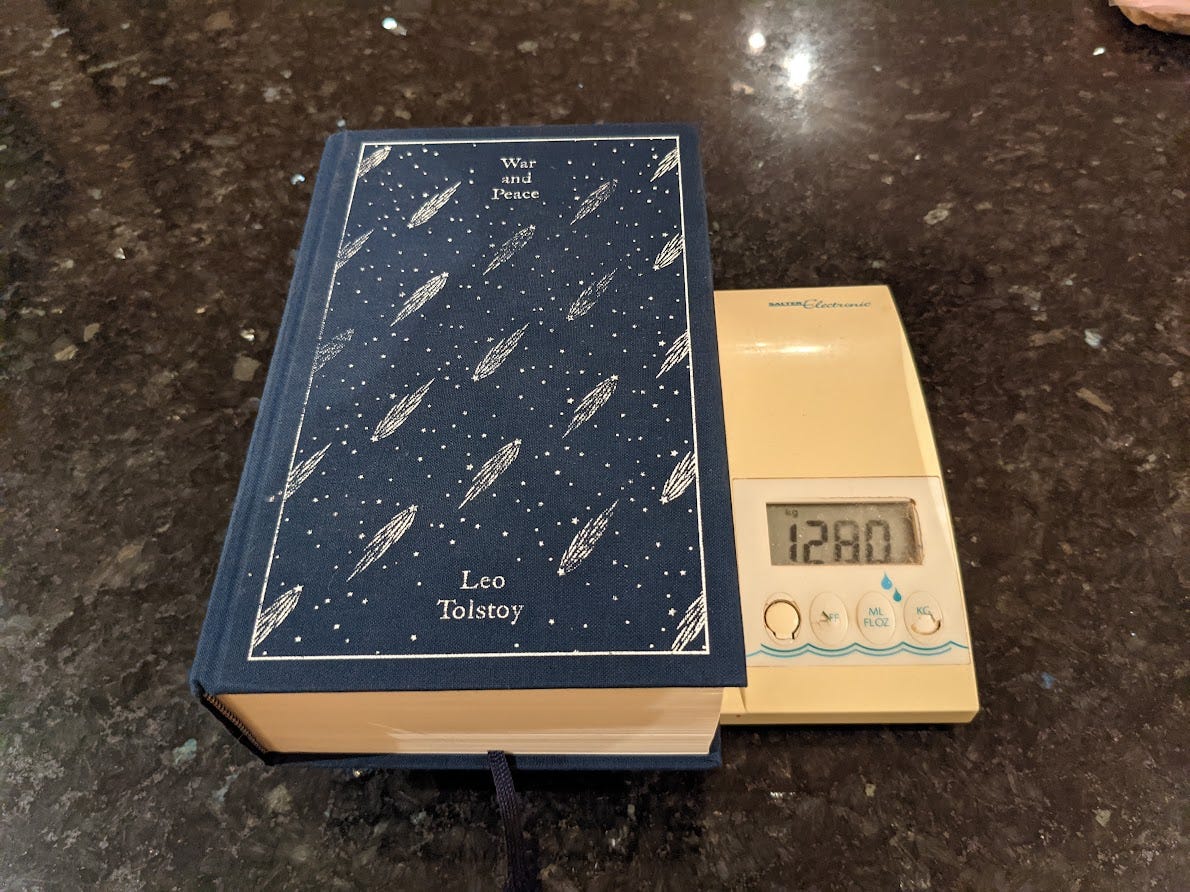

Tolstoy’s 1,358-page tome has two of them, one ending before the epilogue, and the other concluding it.

The former is a disastrously abrupt conclusion in the narrative. That’s resolved in the epilogue, but this in turn ends as an unfulfilling conclusion to reflections on history, free will, and change.

But the thing with books which weigh in at more than a kilo is that an ending is a very small part of it, even if there are two of them. Without a doubt, War and Peace is a beautiful book. Beautiful in the sense that the word ‘beauty’ might have been created for that very piece of prose. The sheer depth that Tolstoy brings to his characters and scenes is both astounding and delightful in particular. Isaac Babel, the 20th-century Russian writer, suggests aptly that “if life could write, it would write like Tolstoy.”

But I do not want to review War and Peace as a piece of fiction. War and Peace, Tolstoy writes, “is not a novel, even less is it a poem, and still less a historical chronicle.” Continuing, he states that “War and Peace is what the author wanted and was able to express.”

That is fitting with most Russian literature. Aleksei Khomiakov, Tolstoy’s contemporary, writes that “to know the world, we have to simplify ourselves intellectually and revert to a mode of immediate apprehension.”1 The modern philosopher, Julian Baggini, suggests that as a result, Russian literature merges with her philosophy, noting that the Soviet dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn “is a philosopher in his native land, but a novelist in (the eyes of the West).”2

Put simply, philosophical insights is the purview of writers as much as it is scholars. “Only in Russia is poetry respected,” wrote Osip Mandelstram, shortly before his death under the Yezhovshchina, Stalin’s cultural purge. In the same tradition, War and Peace is rooted in the immediate world, but with philosophical companions in Europe. Tolstoy said of War and Peace that much of his meaning is written by Schopenhauer in the German’s The World as Will and Representation (1818), which “approaches it (the same topic) from the other side.”3 Tolstoy approaches from experience, or immediate apprehension; Schopenhauer from philosophy. 4

Russian literature is distinctive, but one can also discern the connections to both East and West. For Lesley Chamberlain, the modern historian of Russian culture, Russian thinking can be summed up “in its startlingly consistent rejection of Descartes and the value of cogito ergo sum.” That’s because Descartes’ implied individualism conflicts with the Orthodox ideal of kenosis, a ‘self-emptying’ process that prepares a person to receive God. Indeed, the modern philosopher A. S. Akhiezer claims that the prime driver of Russian thought has been the need to hold Russian society together, “preventing the part falling away from the whole.”5

In this sense, there are shared themes with Chinese philosophy in its emphasis on social harmony, known as he (和).6 That said, it is only in Russian thought which sees individual division as a threat. Chinese philosophy tends to see diversity as a necessity for the purpose of he.7 As the scholar Shi Bo writes in the fifth-fourth-century BC classic Gouyu, “a single sound is not musical, a single colour does not constitute a beautiful pattern, and a single thing does not make harmony.”8

That is an aphorism befitting of Tolstoy, an anarchist and later-atheist who rejects and follows these ideas in equal measure in War and Peace. Narrative-wise, the book trains lenses upon many aspects of nation, society, family, and individuality during the Napoleonic Wars. But the largest focus is reserved Count Pierre Bezukhov, the bumbling fictional protagonist who, blessed into inherited wealth, buffoons through life much like a drunken man bouncing around the safety of his own home, until he falls into a garden of life to discover a desire for purpose, a range of ideas to fill the void, and ultimately a joyful new acceptance of his place in life’s natural harmony.

In this sense, individualism lies at the start of this process and becomes supplemented by an overarching sense of oneness with the world. Fulfillment is found from within the individual, through harmonisation with life on earth as much as through appreciation for a god above.

(You might call this sense of individually-sought harmony one of Empowered Belonging.)

Throughout War and Peace, harmony is one of the key concepts, if not the most significant. On the individual and narrative level it is the story of Pierre, but we also see this on the conceptual level, which Tolstoy approaches via his off-piste philosophical reflections distributed throughout the book. He accesses these reflections through discussions on war, power, and history.

THE PHILOSOPHY OF WAR AND PEACE

Tolstoy was born in 1828, serving as a lieutenant during the Crimean War of 1854-56 against the newly-allied France and United Kingdom, the latter of which had been Russian allies against Napoleon's France not many decades earlier. Appalled by the violence of war, Tolstoy left the army after defeat in Crimea to travel around Europe, where he evolved into a non-violent anarchist.9 In 1857, he witnessed an execution by guillotine in Paris, which marked the rest of his life, and whilst on a second visit in 1861, reviewed a forthcoming book by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, which the French anarchist had titled Le Guerre et la Paix, or War and Peace.

Borrowing the name, it was in this context that Tolstoy wrote the War and Peace we know today, finishing the first draft in 1863. The narrative begins in 1805 with Russia at war with Napoleonic France. Over the following eight years, Russia finds herself allied with, at peace with, but most frequently in conflict with the post-revolutionary country. Beyond the narrative, War and Peace is an interrogation into the methods of historical study, motivated by Tolstoy's desire to understand the historical arc of the Napoleonic era and his own. Why did war happen? Why did allies turn on each other and enemies unite? Why did commanders in safety instruct men in the action?

Before Tolstoy’s time, history had been quite comfortable attributing such events at root to the acts of gods. But historians of Napoleon have no such shortcut; by the 19th-century, history had entered a time of reason and rationality. Historians instead emphasised the concept of Great Men, with books like Thomas Carlyle’s persistently-titled On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History (1840).

For Tolstoy, no concept attracts as much diatribe as this. To him, Great Man theory felt as if one was looking over the bow of a boat to see the cresting waves falling ahead of it, and assuming that these waves were what led the boat forwards, ignorant of the engine rumbling at the stern. Correlation, in other words, does not equal causation.

Looking upon Napoleon’s rapid advance to Moscow and equally rapid withdrawal, Tolstoy sees not heroic genius and chance misfortune, but something bigger, which he calls the ‘collective will’. Power is not randomly distributed, leaving a chronology of Great Men in its wake, but is held equally across the collective of humanity. In turn, power is the delegation of the collective will into the hands of one person.

After the bloodcurdling battle at Borodino (Sept 1812), seventy miles west of Moscow, Napoleon had no choice but to advance further; his army would only accept seizing the city after marching so far. Retreating that December, Napoleon again had no other choice. It is bizarre to say, however, that Napoleon’s genius ‘ran out’ upon reaching the heart of Russia: how could a genius not foresee what would come?

Yet it is genius and heroism that Tolstoy sees his fellow historians, all men of reason and rationalism, suggesting. His disgust permeates the entire book. “All there is in a German head is reasoning,” complains Prince Andrey in the narrative, “which isn’t worth a tinker’s damn.”

Tolstoy reserves his full explanation for the epilogue. “Consciousness is a source of self-awareness independent of reason,” he argues. “Through reason man can observe himself, but he knows himself only through consciousness.” This is an intriguing companion to Descartes’ I think, therefore I am. The Frenchman’s conclusion is inherently one of reasoning, but it is also one that does not distinguish between reason and consciousness as Tolstoy does. Indeed, Descartes rejects the idea that ‘experience’ is a valid form of understanding at all. As we might have inferred from Chamberlain, cogito ergo sum is in many ways the ultimate target of Tolstoy’s ire, which is directed at the pursuit of reason over experience; intellectual complexity over immediate apprehension; theory over practice.

This proliferation of reason, Tolstoy writes, is much like “plasterers assigned to plaster one side of a church wall, who smear their plaster all over the windows and the icons, and rejoice at how, from their plastering point of view, everything comes out flat and smooth.” In teaching this, Tolstoy bears similarities to Carl von Clausewitz, whose treatise On War sets out a seminal contribution to grand strategy: the theoretical map is not the territorial reality; theory alongside practice, in harmony with it.

Understanding this is critical to our understanding of the collective will, which Tolstoy sees as the closest thing we have to a tangible engine of history. It is this that provides the boundaries and force, the form and content, that creates history’s arc.

But if a Great Man’s will is constrained by the collective’s, then this in turn, being composed only of other individuals, must also be constrained. But if our wills are not in fact free, but are “necessarily” determined, then war becomes inevitable.

Tolstoy’s concluding epilogue brings to the surface his efforts to reconcile free will and “determined necessity”, seeking to avoid that conclusion. In doing so, he hopes to identify a general framework through which one can understand how war, alliances, and violence occur — and how to prevent it.

“The problem of man's free will may remain unarticulated, but is felt at every step in history.”

Tolstoy believes that reason, which we rationally know, and is characterised by Descartes and the plasterer, is woefully misused. For it forgets consciousness, which we feel. And consciousness refers to a force no less legitimate than those defined by reason. Tolstoy points to gravity, a scientific ‘law’ which we can predict and express and anticipate perfectly but lies, like consciousness, without a real explanation.

“Reason gives expression to the laws of necessity,” he writes. “Consciousness gives expression to the essence of free will.” I interpret this sentence as something like ‘we don’t understand gravity itself, but it seems to be reflected by these laws, which we can use’. Similarly, we don’t understand free will itself, but our consciousness shows us what it means in practice.

Gravity is an example of determined necessity that is expressed via reason, in this case physics. Free will is equally fundamentally unexplained, and is expressed by our consciousness — which reason cannot understand but we nonetheless apprehend and feel. “Only by bringing them together again do we arrive at a clear concept of human life,” Tolstoy writes.

It is here where the Russian runs alongside Schopenhauer, whose key idea in his book The World as Will and Representation is that a person’s world consists of two things: will, which is the essence of an individual; and representation, which is their interpretation of the reality, defining the boundaries within which an individual exerts their will.

Hence Tolstoy’s phrase, “Free will is content; necessity is form.” Necessity is our reality as we understand it: a space inside which we can exert our free will, which provides content within that space.

Tolstoy also bears similarities with Immanuel Kant, whose Critique of Pure Reason (1781) distinguishes between two realms in the universe: the phenomenal, i.e. phenomena like gravity; and the noumenal, where our consciousness lies.

Following this distinction, Tolstoy nonetheless suggests a slight difference. Specifically, he notes that even sciences of the phenomena have failed to reach the end of the explanatory tunnel, and instead are just finding a new unexplained force behind every cause. For example, instead of understanding what lies behind gravity, we just acknowledge that it works.

The same with history. History is driven by free will, a force of consciousness. This determines the collective will, and thus the arc of history, and thus why wars happen. But instead of seeking the impossible insight of what lies behind free will, Tolstoy suggests that history should focus on identifying the laws that anticipate how will is freely expressed. Easy, right?

HARMONY AND CHANGE

Once you realise that War and Peace is full of antitheses, it’s hard to stop finding them. War and peace; city and country; St Petersburg and Moscow; international movements and individual stories. Ditto for the more conceptual aspects of the book: form and content; reason and feeling; theory and practice; necessity and free will.

This is related to the intellectual climate of nineteenth-century Russia, in which, dialectically, an argument began with a moment of understanding, was then met by a moment of instability, and ultimately reaches a higher level of truth. Peace is destabilised by war, only to synthesise into a broader understanding of how the two interact. Theory is destabilised by practice, but they synthesise to identify the correct course of action. Barely any of Tolstoy’s book is spent at peace, but it is critical for understanding war. A single note does not make harmony, and individual actions only succeed when in harmony with the broader context.

But Tolstoy never finds the synthesis he seeks between free will and necessity. Through interrogating the arc of history, we are left only with the collective will, and in exploring how this manifests from the individuals who make up the collective, Tolstoy exhausts himself, overwhelmed by “the equal and inseparably interconnected, infinitesimal elements of free will.” And thus the book closes for the last time with the reluctant phrase: “we must accept a dependence that we cannot feel.”

John Lewis Gaddis, the modern American historian, notes how Tolstoy, alongside Clausewitz, foreshadows the development of chaos theory, the study of apparently random behaviour in systems predicted by consistent laws. The kind of laws that could anticipate how will is freely expressed.

Gaddis suggests that Tolstoy “sensed the nature of complexity before he had the words to express it.”10 But in his attempt to bring practice on par with theory, synthesise reason and feeling, and find compatibility between free will and necessity, Tolstoy reminds us that “only by bringing them together again do we arrive at a clear concept of human life.” And that in itself is valuable.

Quotes I enjoyed

I read Anthony Briggs’ 2005 translation. These are two important quotes.

Page 894, on leadership and the collective will, during the Battle of Borodino. Tolstoy admires Kutuzov’s actions during the war, and creates an example of how leadership should focus on the collective will that governs above a leader, rather than optimising the relatively meaningless decisions that a leader might take charge of below.

Kutuzov listened to reports as they came in and responded to any requests for instructions from subordinates, but as he listened he didn't seem very committed to what was being said; he seemed more interested in some aspect of the speaker's facial expression or tone of voice. Long years of military experience had told him that one person cannot control hundreds of thousands of men fighting to the death, and he knew that the fate of battles is not decided by orders from the commander-in-chief, nor by stationing of troops, nor the number of cannons of enemies killed, it is decided by a mysterious force known as the ‘spirit of the army’.

Page 1,080, on happiness, in the period in which Pierre is amongst those held prisoner by the French. It is a key moment that marks Pierre’s evolution into a man at harmony with the world, having learnt to accept the chaos that characterises life:

Karatayev enjoyed no attachments, no friendships, no love, yet he loved and showed affection to every creature he came across in life, especially people, no particular people, just those who happened to be there before his eyes. He loved his dog, his comrades, the French, and he loved Pierre, his neighbour. But Pierre felt that for all the warmth and affection that Karatayev showed him, he wouldn’t suffer a moment’s sorrow if they were to part.

Further reading

There are two major questions in War and Peace. What is life? How can we predict it?

If you’re interested in What is life? then read Gaddis’ 12 page essay on War, Peace, and Everything. It is an overview on how Tolstoy, amongst others, tie into later understandings of chaos, and thus help us understand life.

If you’re interested in How can we predict it? then read Noahpinion’s blog on The Third Magic. It is an overview on how we will navigate the “interconnected, infinitesimal elements of free will” without understanding it, and thus predict life.

Lesley Chamberlain, Motherland: A Philosophical History of Russia (Atlantic Books, 2004: 41)

Julian Baggini, How The World Thinks (Granta Books, 2019: 334)

The are multiple ways to interpret this. One other is on the question of happiness. Tolstoy approaches his conclusions on what drives history with happiness; finding joy in the fact that one can change little. Schopenhauer approaches this as something to be put-up with, rather than embraced. Of Tolstoy and Schopenhauer, I have only read War and Peace, but I think by “other side”, the former distinguishes between philosophical approaches, rather than happiness and unhappiness.

Eimear McBride, Stalin and the Poets, New Statesman, May 9th 2017

Lesley Chamberlain, Motherland: A Philosophical History of Russia (Atlantic Books, 2004: 203)

Chenyang Li, The Confucian Philosophy of Harmony (Routledge, 2014: 1)

This seems in stark contrast with current events, but do not mistake a century of Chinese government for twenty centuries of Chinese thought. As Tolstoy writes admirably of General Kutuzov on page 1,208, “he viewed today’s events with tomorrow’s significance.” Do not get caught up in the contemporary, for there is much more than the present.

Kehong Lai, The Guoyu Interpreted (Fudan University Press, 2000)

A. N. Wilson, Tolstoy (W. W. Norton & Company, 1988: 146)

John L. Gaddis (2011): War, Peace, and Everything (Cliodynamics 2(1): 50)