Social Mania and Civilisational Maturity (or, why are all the cults American?)

Does the framework of ‘Europe did class war, America does social justice’ help us understand the difference between these two parts of the world?

I haven’t written for a while. Trying to get more into it with some big pieces following up on my Folklore essay and also exploring how my thinking has changed since I first started worrying about AI and everyone’s jobs in 2019 (things moved quicker than expected but there is hope).

In the interim, I wrote this short piece about social manias and wanted to get something out in the world, particularly as I’ve received a bunch of new subscribers recently (welcome!).

I think it’s fair to say that cult-like movements are far more common in the US than Europe. Why?

When I say ‘cult-like’ and ‘mania’, I’m thinking of social movements, not economic ones. In a social movement, wealth and class has little impact on someone’s participation, but this is pivotal to how someone engages with an economic movement (like a trade union or a strike). Of course, finance lies square in the middle and all social movements come with large (mis)allocations of economic value; financial manias from tulips to memecoins lie in this category.

As far as I know, Europe hasn’t been a hotbed for this since the Industrial Revolution.

Witch-hunts are probably the most severe example of social mania in history, whilst financial bubbles for tulips and more were common, yet manias like this seemed to die out from the 1800s: Pineapple fever never reached similar heights. Neither did manias for railways and bicycles, and these brought productive infrastructure and innovation anyway, making them to some extent more sustainable.

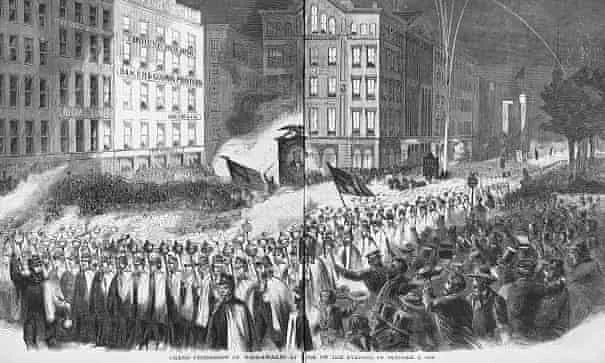

Europe didn’t have groups like the Wide-Awakes, a 500,000-strong abolitionist youth movement that sprang up in the American North just before the civil war. East of the Atlantic meanwhile, Europeans were immiserated by the Industrial Revolution and were overthrowing governments from France to Hungary (1848) — this is more class war than social movements.

I think that hints at why we see cult-like movements more often in the US. The Industrial Revolution destroyed an entrenched way of life in Europe, whereas American culture had less to overwrite. This lasted for 50+ years (multiple generations), and Europeans would have had a stronger sense of loss. Real wages in Europe were stagnant from 1770 to 1840, and quality of life declined in the early throes of urbanisation.

Not only would this fuel attitudes for class war, but it probably engenders a much more pragmatic approach to social manias like Q-Anon (and a less heady impression of god). By contrast, if you haven’t experienced such prolonged economic distress, you’re not going to need class war to improve your place in the world. The Great Depression lasted 15 years, max.

At the same time, North America for a long time was a case of ‘we’re building this together’, and that spirit largely engenders today. Europeans seem more measured and less willing to go all in. Americans identify much more closely with the success of the protocol and embrace the concept of contributing to something they want to exist in the world.

This got me thinking more broadly. Would a multi-generational period of stagnation (for most families, not the economy as a whole) reshape American society to be more European/matured? And this threatened by AI? In some views, American wages have stagnated for decades since the 1970s, so is this on the way again?

Does this framework of ‘Europe did* class war, America does social justice’ help us understand many of the differences between the two parts of the world?

*obviously Europe graduated from the class war period of civilisation in 1945, and is now better understood as some other meta; like internationalism.

And by contrast, a propensity for manic bubbles can unlock step-change progress for all. This happened with railways in the 1800s, but not since in Europe. More recently, We see similar in the US, with the dot com bubble and now AI data centres. The European determination to end class conflict is usually seen as harming growth via a ‘socialist bad incentives’ logic, but the immiserating source of that class conflict (Europeans having a terrible time in the early 1800s) may have turned societies against that kind of visceral boom and bust for centuries. A propensity for social manias tells us more than we think.

I wrote this very spontaneously. Do you think I’ve interpreted the evidence right? Does the logic stack up? What have I missed?